Making Black Cultural Heritage Visible

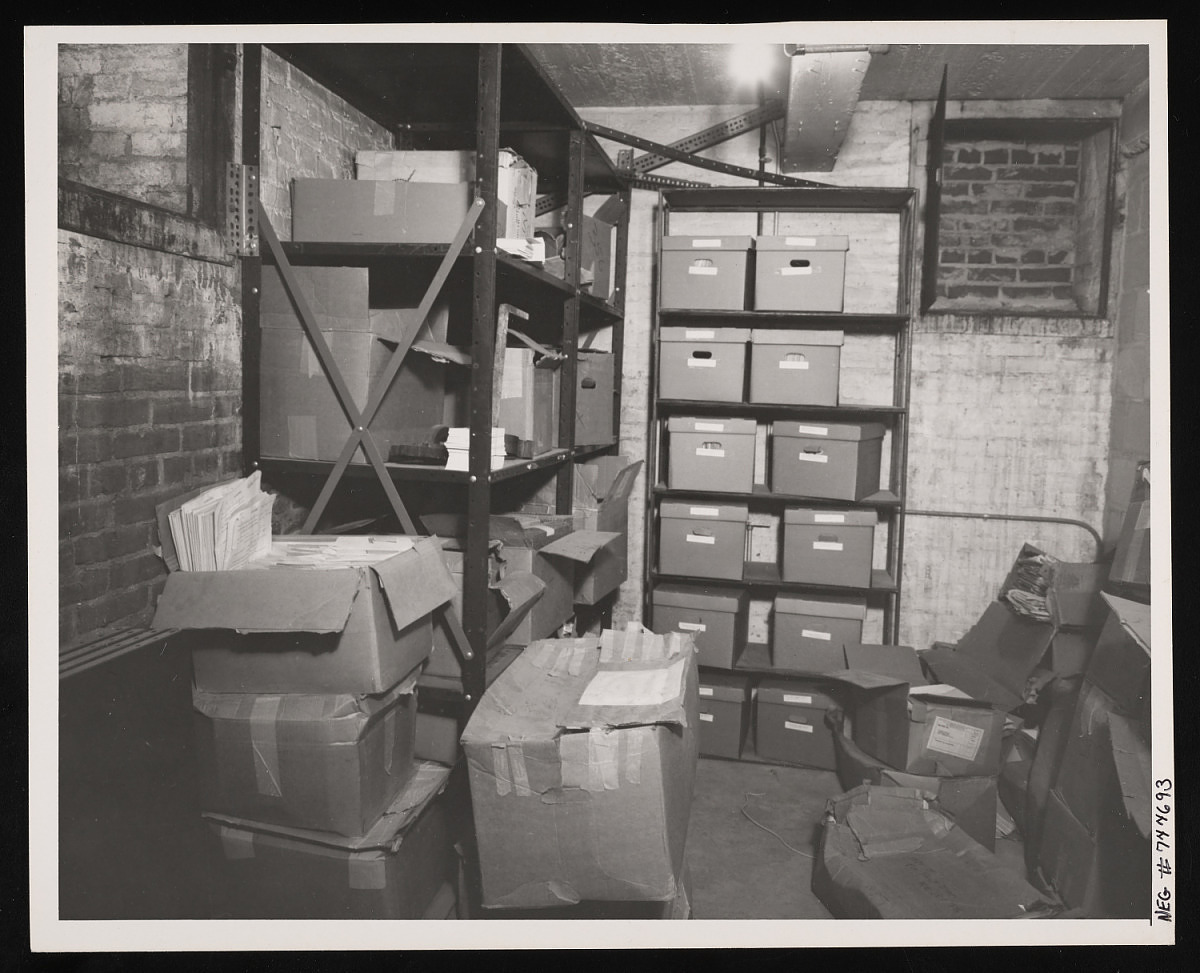

- Interior view, fifth floor, East Tower North of the Smithsonian Institution Building, or Castle, looking south, with storage boxes and shelving in view. This media is in the public domain (free of copyright restrictions), Smithsonian Institution Archives.

I want to draw attention to archivist and curator Dorothy Berry’s passionate essay “The House That Archives Built.” In this writing, she unpacks her fraught relationship with institutional archives and with the professional discipline in which she was trained. She speaks from personal experience as a Black woman from the Missouri Ozarks where her father had created and ran a museum to share his own cultural heritage. This personal experience provided her with an awareness that contrasted and conflicted with professional structures and systems that determine how artifacts are categorized and described. In doing so, they also determine what—and whose—culture is seen or not seen. They render certain history invisible and, in doing so, uphold a worldview of white supremacy. As the saying goes, if you have a [White] hammer, the whole world looks like [White] nails.

As Berry states in her personal website bio, “Cultural heritage materials open the door to history in visceral and unfettered ways. I am committed to a career of expanding access to those materials through creative and innovative ways focusing on digital and physical methodologies that unite stakeholder communities with their often displaced heritages.”

In her essay, Berry speaks forcefully about the reform of her discipline and its practices. It is an important step toward a broader awareness of institutional practices that preclude visibility and recognition of Black experiences in the past. While The People’s Graphic Design Archive is a different animal than a physical archive, we hope that our approach is a “creative and innovative” way towards greater preservation and acknowledgment of Black cultural heritage. In our case, it is a heritage that comes in the form of graphic design. But the larger agenda is to present an alternative to this heritage as White (as well as male and European). We joyfully recognize the contributions that have remained unacknowledged and invisible for too long. We encourage everyone to add those contributions to PGDA and through imaginative tagging increase the visibility, relevancy, and meaning of work created by Black designers and about the many Black communities that are part of our culture.